| Year | Arab | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 267 | |

| 1944/45 | 200 |

| Year | Arab | Public | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1944/45 | 6735 | 6735 |

| Use | Public | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1693 | 1693 (25%) | |||||||||

|

5042 | 5042 (75%) |

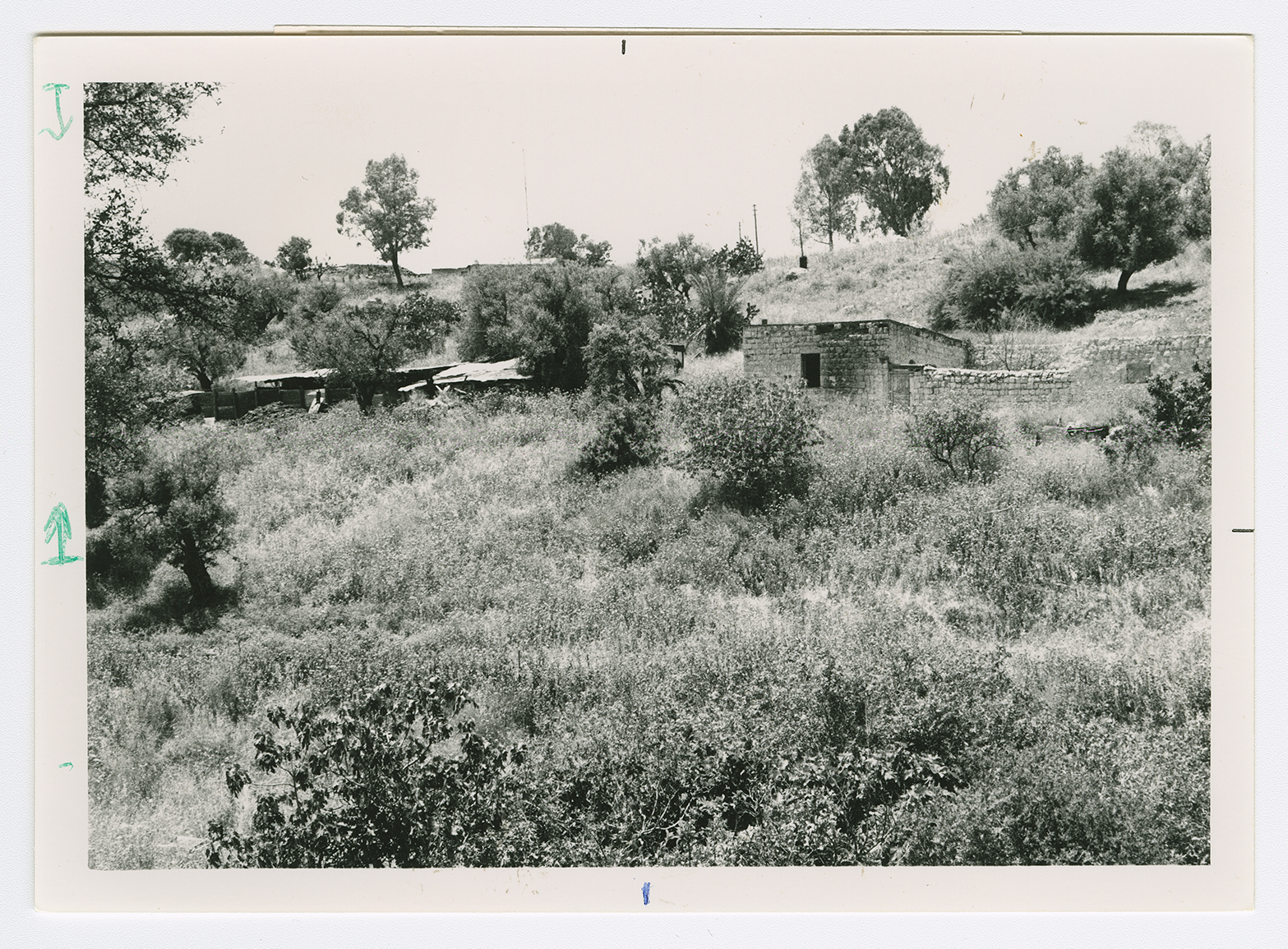

The village was situated on the volcanic sill that formed the southern border of the al-Hula Plain. It was about 1 km west of the Jordan River, and was linked by a secondary road to the highway leading to Safad and Tiberias. The composite name of the village was probably derived from two sources: 'al-Khayt' from the region on the southwestern edge of Lake al-Hula, known as ard al-khayt, in which it was located (see Robinson 1841:341); and 'Mansura' after a Shaykh Mansur, who according to tradition had been buried there. It was also called Mansurat al-Hula, to distinguish it from another village by the same name, al-Mansura (see al-Mansura, Safad sub-disctrict). The Arab geographer al-Dimashqi (d. 1327) wrote that the diyar (territories) of al-Khayt were located in the Jordan Valley and were similar to the land of Iraq because of their rice, birds, warm water, and agricultural crops. Subsequently, the Syrian Sufi traveler al-Bakri al-Siddiqi, who visited the area in the mid-eighteenth century, related that he passed by al-Khayt with the judge of Safad.

Under the Mandate, Mansurat al-Khayt was a hamlet (so classified by the Palestine Index Gazetteer) whose entire population was Muslim. Agricultural production and animal husbandry were the mainstays of its economy.

The village first came under attack by the Haganah on 18 January 1948, well before widescale fighting had broken out. Israeli historian Benny Morris notes that it 'was temporarily evacuated during a Haganah retaliatory strike,' but he does not say what triggered the alleged retaliation. He also neglects to mention the number of casualties left by the raid and the date the villagers returned after their temporary exile. Another raid followed on the heels of the first one, on the night of 6-7 February. The New York Times reported: 'During the night fifty Jews made well-organized attacks on the Arab village of Mansurat el Kheit ... with automatic arms. They blew up a house under cover of heavy fire from automatic weapons .... ' One villager was reported wounded. An official British communique quoted in the Palestinian daily Filastin confirms this report.

However, if any villagers left as a result of the attacks, they apparently returned soon afterwards, since Israel made a concerted effort to evict them from 1949 until 1956. In July 1949, the armistice agreement was signed between Israel and Syria, according to which the village fell in the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) along the border. As such, its residents were protected by the agreement and could not be expelled. However, over the next several years Israel used a variety of methods to turn the villagers out of their homes, eventually succeeding in pushing them into Syria (see Kirad al-Baqqara, Safad sub-disctrict). In the case of this and at least seven other villages in the DMZ, the reasons given for the proposed expulsions were 'military, economic and agricultural.'

There are no Israeli settlements on village land. The settlement of Kefar ha-Nasi' (206264), founded in 1948, lies nearby to the west, on land belonging to the (still-existing) village of Tuba (206263).

The site is partly wooded and partly overgrown with grass; no landmarks are visible. The surrounding land is farmed by the settlement of Kefar ha-Nasi'.