| Year | Arab | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 674 | |

| 1944/45 * | 1000 | 1000 |

| Year | Arab | Public | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1944/45 * | 12548 | 6015 | 18563 |

| Use | Arab | Public | Total | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

*includes Suruh, al-Nabi Rubin **includes Suruh, al-Nabi Rubin |

8729 | 6011 | 14740 (79%) | ||||||||||||

*includes Suruh, al-Nabi Rubin **includes Suruh, al-Nabi Rubin |

3819 | 4 | 3823 (21%) |

The village was situated on the flat part of a plateau that rose gradually toward the west, bordered by a wide wadi. It overlooked its two satellite villages to the east: Suruh and al-Nabi Rubin. A network of secondary roads linked it to Ra's al-Naqura and some neighboring villages along the Lebanese border. Tarbikha was located on the site of the Crusader 'Tayerebika,' from which it derived its name. In 1596, Tarbikha was a village in the nahiya of Tibnin (liwa' of Safad), with a population of 88. It paid taxes on a number of crops, including wheat, barley, and olives, as well as on other types of produce and property, such as goats and beehives and a press that was used for processing either olives or grapes.

In the late nineteenth century, the village of Tarbikha was built of stone and was situated on a ridge. The village's 100 residents cultivated olives. Tarbikha was part of Beirut province in the late Ottoman period. It was not until after World War I, when the borders between Lebanon and Palestine were delineated by the British and French, that Tarbikha came under Palestinian administration. The population consisted entirely of Muslims. The houses of Tarbikha were made of stone, with wood–and–mud ceilings, and clustered initially around a watering pool. Some two–storey houses, built of reinforced concrete, appeared in the village toward the end of the Mandate, and new construction stretched along the Ra's al-Naqura–Banat Ya'qub road. The village had two mosques and an elementary school, founded after 1938, that had an enrollment of 120 students in the mid–1940s. It also had a customs office and a police station for monitoring the Lebanese border. A Cultural Reform Association (jam'iyyat al-islah al-thaqafiyya) was founded in Tarbikha in 1945 to improve social, educational, and medical conditions.

The village land was mountainous and cut by several wadis, but it also had several flat areas. Springs, reservoirs, and wells provided the inhabitants with water for domestic use. The bulk of the land area was used as pasture, but the villagers also grew grain, olives, and other crops. Tobacco production increased toward the end of the Mandate and its quality began to match that grown in Turkey. In 1944/45 a total of 3,200 dunums was allotted to cereals; 619 dunums were irrigated or used for orchards.

Numerous khirbas on the village lands have been identified which provide evidence for a rich and long history of habitation in the immediate area. Some khirbas contained ancient olive presses and rock–hewn tombs.

After the completion of the Israeli army's Operation Hiram, at the end of October 1948, Israeli units swept into a number of villages near the border with Lebanon and expelled their inhabitants. Tarbikha was one of the first to be captured. Some time during the second week of November, the Oded Brigade entered the village and ordered its people to cross the border into Lebanon. The Israeli forces met with no resistance in the village, according to the account of the occupation in the History of the War of Independence. Nevertheless, Israeli historian Benny Morris quotes the Israeli commanding officer of the Northern Front as saying that his forces 'had been forced for military reasons' to expel the villagers of Tarbikha, among others.

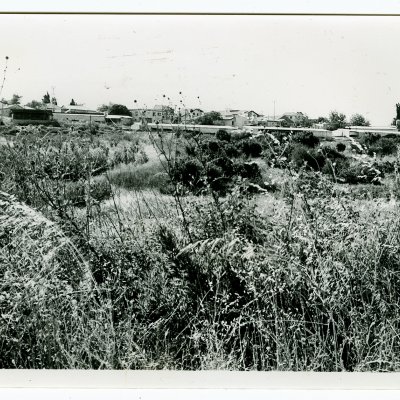

Morris states that by 27 May 1949, Jewish immigrants had been settled in the village, which was renamed Shomera. Even Menachem, established in 1960, is located very close to the village site. Netu'a, founded in 1966, Kefar Rosenwald, established in 1967, and Shetula, founded in 1969, are also on village lands.

About twenty houses from the village are now occupied by the residents of Moshav Shomera. Some of the roofs have been remodeled and given a gabled form. Stones from the original houses embellish the roof of the central shelter of the moshav.