| Year | Arab | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 428 | |

| 1944/45 | 610 | 610 |

| Year | Arab | Jewish | Public | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1944/45 | 2701 | 153 | 3 | 2857 |

| Use | Arab | Jewish | Public | Total | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1945 | 43 | 3 | 1991 (70%) | |||||||||||||||

|

756 | 110 | 866 (30%) |

The village was built on the eastern slopes of a hill, the peak of which was some 800 meters in height and commanded a wide view all around. It faced the western suburbs of Jerusalem―about 1 km away―from which it was divided by a terraced valley planted with fig, almond, and olive trees. Along the northern rim of the valley ran a secondary road that linked Deir Yasin to these suburbs and to the main Jerusalem−Jaffa road about 2 km to the north. 'Dayr' [Deir] denotes a 'monastery' in Arabic. This was not an uncommon component of Palestinian village names and is hardly surprising in a village so close to Jerusalem. There was in fact a large ruin at the southwestern edge of the village which was known simply as the 'Dayr' [Deir].

It appears that the nucleus of the settlement in early Ottoman times was at Khirbat Ayn al-Tut―'The Mulberry Spring Khirba'―some 500 m to the west of the 1948 village site. In 1596 the village of Khirbat Ayn al-Tut was in the nahiya of Jerusalem (liwa' of Jerusalem) with a population of thirty-nine. It paid taxes on wheat, barley, and olive trees .

We do not know precisely when the settlement shifted to the site of Deir Yasin. But it is obvious that the name of the latter is partly derived from a Shaykh Yasin whose tomb was in a mosque named after him that stood close to the ruins of the Dayr [Deir]. We do not, however, know much about the Shaykh, nor when his mosque was built.

In the late nineteenth century the houses of Deir Yasin were built of stone. Two springs, one to the north and the other to the south provided the village with water. Most of its houses, strongly built with thick walls, were crowded together in a small area separated by narrow winding lanes, known as the Hara ('The Quarter'). All the inhabitants of Deir Yasin were Muslim. In about 1906 the westernmost Jewish suburb of Jerusalem, Giv'at Sha'ul, was built across the valley from Deir Yasin to be followed respectively by those of Montefiore, Beit Hakerem, and Yefenof. The secondary road linking Deir Yasin to Jerusalem and the road to Jaffa ran through Giv'at Sha'ul.

During World War I the Ottomans fortified the hilltop of Deir Yasin as part of the defense system of Jerusalem. On 8 December 1917, these fortifications were stormed by troops under the command of General Allenby in the final offensive that led, on the following day, to the fall of Jerusalem to Allied hands.

Until the 1920s, Deir Yasin's livelihood largely depended on agriculture, supplemented by the keeping of livestock, but the building boom in Jerusalem under the Mandate quickly changed the basis of its economy. The area around Deir Yasin was rich in limestone―the favorite building material in Jerusalem. Early in the Mandate the villagers excavated extensive quarries along the length of the secondary road leading to the city and developed an increasingly thriving industry in stone cutting and processing. By the late 1940s, four stone crushers were functioning. The business encouraged the more prosperous villagers to invest in trucking and others to become truck drivers. In 1935, a local bus company was established in a joint venture with the neighboring village of Lifta (Jerusalem sub-disctrict). As Deir Yasin prospered its houses radiated from the Hara uphill and eastward, towards Jerusalem.

In the early days of the Mandate the village had no school of its own and its children attended the school at Lifta or Qalunya (Jerusalem sub-disctrict). By 1943 Deir Yasin could boast of an elementary school for boys and in 1946 of one for girls both built by village contributions. The girls' school had a resident headmistress from Jerusalem. The village also had a bakery, two guest-houses, a social club ('The Renaissance Club'), a thrift fund, three shops, four wells, and a second mosque on the higher slopes overlooking the village built by one Mahmud Salah, an affluent villager. By the end of the Mandate, many villagers were employed outside Deir Yasin, some in the nearby British army camps as waiters, carpenters, and foremen; others as clerks and teachers in the mandatory civil service. By this time no more than 15 percent of the village population was engaged in agriculture.

Deir Yasin's population had increased from 428 in 1931 to 750 in 1948 and its houses from 91 in the former year to 144 in the latter. Relations between the village and its Jewish neighbors had started reasonably well under the Ottomans, particularly early on when Arabic-speaking Sephardic Yemenite Jews comprised much of the surrounding population. But their relations rapidly deteriorated with the growth of the Jewish National Home and reached their nadir during the Great Rebellion of 1936−39. Relations picked up again during the boom years of full employment of World War II. Thus in 1948 Deir Yasin was a prosperous, expanding village at relative peace with its Jewish neighbors with whom much business was done. Both Deir Yasin and Khirbat Ayn al-Tut contained archeological evidence of previous habitation: walls, arches, cisterns, and tombs.

Deir Yasin was the site of the best-known and perhaps bloodiest atrocity of the war. Although the massacre was carried out by the Irgun Zvai Leumi (IZL) and Stern Gang (LEHI), the occupation of the village fell within the general framework of the Haganah's Operation Nachshon. A Palmach unit with mortars took part in the assault after the villagers had brought to a halt the initial surprise attack by the IZL and LEHI forces. The History of the Haganah states that David Shaltiel, the Haganah's Jerusalem commander, learned of the IZL-LEHI plan to attack Deir Yasin. He informed the commanders of these groups that the occupation and retention of the village were a part of the general Haganah plan in Operation Nachshon, although Deir Yasin had signed a nonaggression agreement with the Haganah. He added that he had no objection to their implementation of the task, provided the IZL-LEHI forces could hold on to the village. If they were unable to do so, he warned, they should not partially destroy the village, as this would encourage the enemy to convert it into a military base. Shaltiel later conceded that, in response to requests made in the course of the attack, he had supplied the attacking units with ammunition for rifles and Sten guns and had provided them with mortar cover.

At the time, the New York Times correspondent reported: 'Twenty men of the [Jewish] Agency's Haganah militia reinforced fifty-five Irgunists and forty-five Sternists who seized the village.' The Haganah stated that at dawn on 9 April 1948, 120 men (80 from IZL and 40 from LEHI) began an assault on the village. According to that account, 4 of the attackers were killed while storming the village. The History of the Haganah mentions that they carried out a massacre 'without discriminating among men and women, children and old people. They finished their work by loading some of the 'prisoners' who had fallen into their hands onto cars and parading them in the streets of Jerusalem in a 'victory convoy,' amidst the cheers of the Jewish masses. After that, these 'prisoners' were returned to the village and killed. The victims included men, women, and children, a total of 245 people.' The New York Times reported that about half of the victims were women and children; another 70 women and children from the village were carried off and later turned over to the British army in Jerusalem.

After the massacre, the Irgunists and Sternists escorted a party of US correspondents, including one from the Times, to a house at the nearby settlement of Giv'at Sha'ul. Over tea and cookies, the perpetrators 'amplified the details' of the operation. They said that ten houses had been blown up in the village and that the attackers blew open doors and threw hand-grenades into others. A spokesman for the attackers said that the village was 'under control' within two hours, adding that he expected the Haganah to take over the village. The spokesman's claim was contradicted by the fact that, five hours into the attack, the IZL and LEHI forces appealed to the Haganah for help. The New York Times reported initially that the Haganah took over the occupation of Deir Yasin the day after the massacre, on 10 April, but the paper later said that they 'formally' occupied the village on 11 April. 'We will maintain the graves and remaining property…,' a Haganah statement proclaimed, 'and return it to the owners when the time comes.' The previous day, a member of the Arab Higher Committee had been quoted as saying that he had appealed in vain to the British police and army for the return of the victims' bodies for burial.

The massacre was subsequently condemned by the main Zionist authorities, including the Haganah, the Jewish Agency, and the Chief Rabbinate. Deir Yasin soon became a byword for the atrocities committed during 1948, and the impact of the massacre on the exodus of the Palestinians in that year has become the subject of intense controversy in Israeli and Palestinian circles.

In the summer of 1949 several hundred Jewish immigrants were settled near Deir Yasin and the new settlement was named Giv'at Sha'ul Bet, after the older settlement of Giv'at Sha'ul which had been established in 1906. Four prominent Israeli intellectuals wrote to Ben-Gurion, asking that the village be left empty as a 'terrible and tragic symbol.' But their repeated appeals went unanswered. Present at the dedication ceremony of Giv'at Sha'ul Bet were several cabinet ministers, the two chief rabbis of Israel, and the Jewish mayor of Jerusalem. The Jewish neighborhood of Giv'at Sha'ul has now spread over the eastern sector of the village. Today the hill of Deir Yasin and its site are engulfed on all sides by the urban spread of Israeli West Jerusalem.

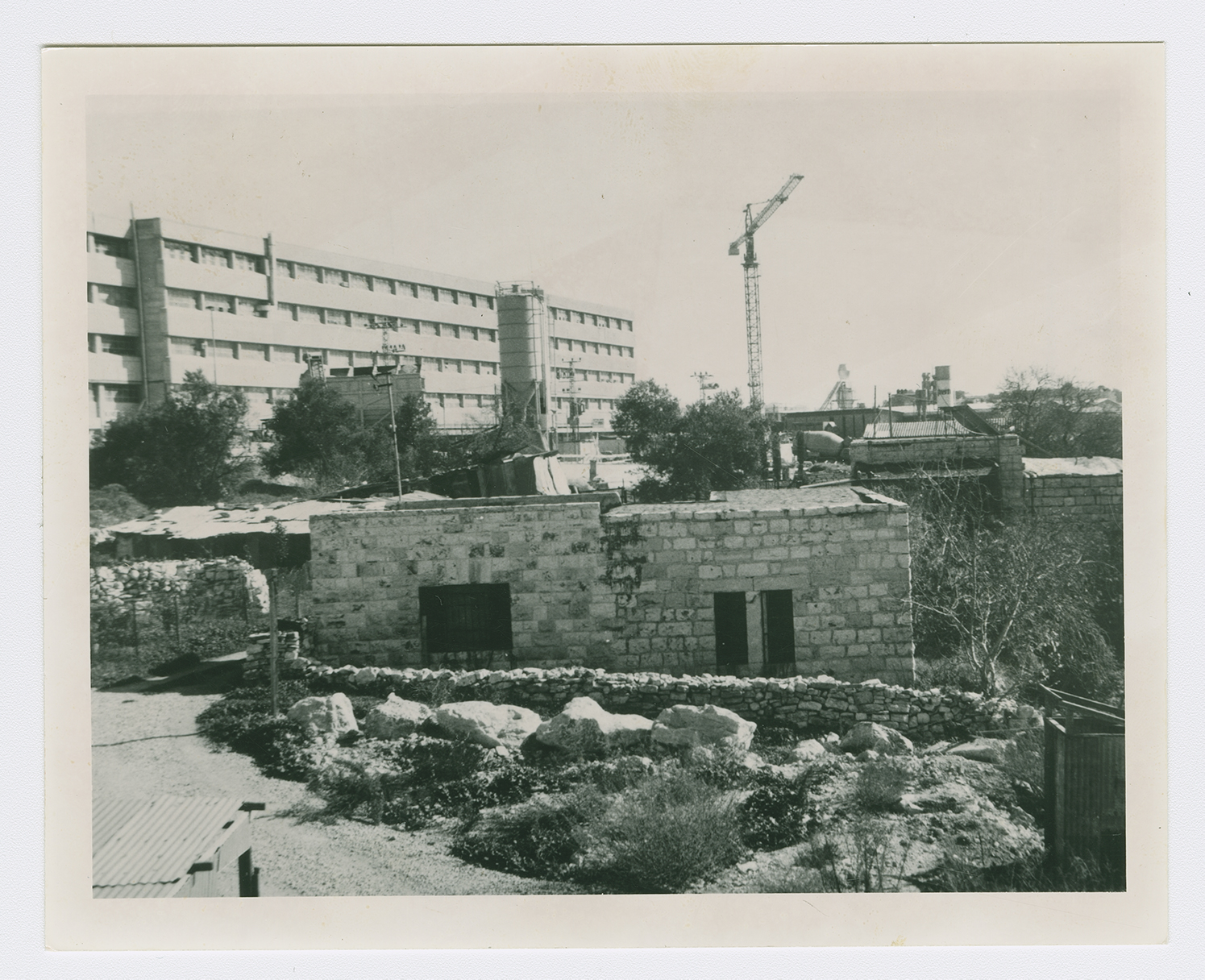

Many of the village houses on the hill are still standing and have been incorporated into an Israeli hospital for the mentally ill that was established on the site. Some houses outside the fence of the hospital grounds are used for residential and commercial purposes, or as warehouses (see photos). Outside the fence, there are carob and almond trees and the stumps of olive trees. Several wells are located at the southwestern edge of the site. The old village cemetery, southeast of the site, is unkempt and threatened by debris from a ring road that has been constructed around the village hill (see photo). One tall cypress tree still stands at the center of the cemetery.

Related Content

Violence

Operations Nachshon and Har'el to Open Tel Aviv-Jerusalem Road

1948

3 April 1948 - 21 April 1948

Popular action

Great Palestinian Rebellion, 1936-1939

A Popular Uprising Facing a Ruthless Repression

New road around the southern border of the village, looking north. The ruins in the foreground are those of the dayr ("monastery'') after which the village was named.

The school of Deir Yasin for boys, looking south on the road from Giv'at Sha'ul to Giv'at Sha'ul Bet. The Hebrew sign on the school building reads: "Home of Chabad Lubovitch at Giv'at at Sha'ul Harnof."

One of the village houses, now occupied by Israelis.

Remains of the village cemetery at the southeastern corner of the village, looking towards the west. Debris from the road that winds around the village (see photo #1) has fallen over the graves.

The entrance to Deir Yasin showing a village house which is now part of the hospital. The Hebrew sign reads: "State of Israel. Ministry of Health."

Former village houses on the road into Deir Yasin. Modern commercial buildings appear in the background. View to the east.