| Year | Arab | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 1893 | |

| 1944/45 | 2550 | 2550 |

| Year | Arab | Jewish | Public | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1944/45 | 7780 | 756 | 207 | 8743 |

| Use | Arab | Jewish | Public | Total | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

4532 | 468 | 207 | 5207 (60%) | |||||||||||||||

|

3248 | 288 | 3536 (40%) |

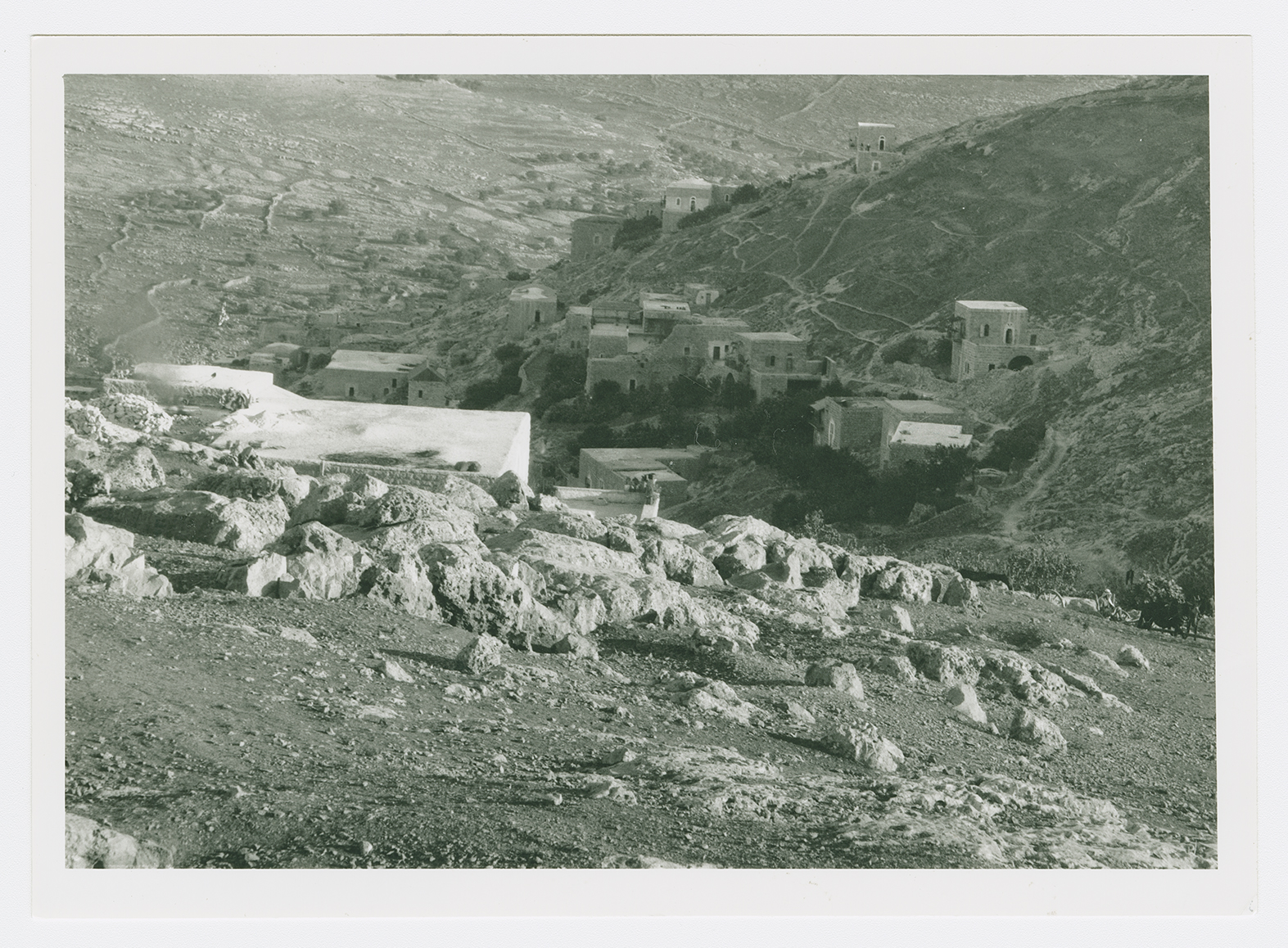

The village stood on the slope of a steep hill and faced north-northwest, overlooking Wadi Salman. The Jerusalem−Jaffa highway ran immediately southwest of it, and dirt paths linked it to a group of neighboring villages. Although the identification of the village has been debated by biblical scholars, Lifta is believed to have been established on the site of Mey Neftoach (Mey Nephtoah), a source of water near Jerusalem (Joshua 15:9, 18:15). The site retained this name during the Roman period and was called Nephtho during the Byzantine era. Almost nothing is known about the village in the early Islamic period; however, during the Crusades the village was referred to as Clepsta. In 1596, Lifta was a village in the nahiya of Jerusalem (liwa' of Jerusalem) with a population of 396. It paid taxes on a number of crops, including wheat, barley, olives, and fruit, as well as on orchards and vineyards. In 1834, the village was the site of a battle in which the Egyptian army under Ibrahim Pasha defeated local rebels led by a prominent local ruler, Shaykh Qasim al-Ahmad.

The family of Qasim al-Ahmad remained powerful, however, for years after this battle. They ruled the region southwest of Nablus from their fortified villages (Dayr Istiya' and Bayt Wazan) some 40 km due north of Lifta.

In the late nineteenth century, Lifta was situated on the side of a steep hill, with a spring and rock-cut tombs to the south.

The village houses were built mainly of stone, along the contours of the hill. The old streets of the village also ran in curvilinear fashion. The village expanded markedly towards the end of the Mandate; construction spread east, up the slope of Mount Khallat al-Tarha, linking the village with the buildings of the Rumayma neighborhood in the northwestern quarter of West Jerusalem. Construction also expanded towards the foot of the hill in the south and southwest, along the Jerusalem−Jaffa highway. Lifta's population was predominantly Muslim; its Christian residents were estimated at 20 out of a total of 2,550 in the mid-1940s. The village had a mosque, a shrine for Shaykh Badr (a local sage), and a few shops at its center. It also had an elementary school for boys and a girls' school that was founded in 1945. There were, in addition, two coffeehouses and a social club. The village was in effect a suburb of the city of Jerusalem, and its economic ties with the city were strong. The farmers of Lifta marketed their produce in Jerusalem markets and took advantage of the city's services. Their drinking water was drawn from a spring in Wadi al-Shami. Their lands were planted in grain, vegetables, and fruit, including olives and grapes; olive trees covered 1,044 dunums. The rainfed agriculture of the village was concentrated in Wadi al-Shami, in the depressions lying to the southwest of the village, and on the slopes. In 1944/45 a total of 3,248 dunums was planted in cereals.

The fighting in Lifta, as well as the adjacent Jerusalem sub-disctricts of Rumayma and Shaykh Badr, was triggered by the Haganah in the earliest days of the war. The History of the Haganah states that, 'Securing the western exit of the city [of Jerusalem] entailed the eviction of Arabs from Romema and Shaykh Badr. Afterwards, the Arabs also vacated Lifta.' Other sources supply further details. According to Israeli historian Benny Morris, the Haganah fired the first shots in December 1947, killing the Palestinian owner of a filling station in Rumayma, on the grounds that he was suspected of informing Arab forces about the departure of Jewish convoys to Tel Aviv. The next day, a grenade was thrown at a Jewish bus. Palestinian historian Aref al-Aref adds that a coffeehouse in Lifta was attacked on 28 December with Sten guns and submachine-guns, and that six of the patrons were killed and seven wounded. The New York Times account puts the number of dead at five, adding that members of the Stern Gang halted their bus outside the cafe, sprayed the patrons with machine-gun fire and threw grenades.

AI-Aref writes that most of the residents of Lifta left after the attack on the coffeehouse and the rest evacuated soon afterwards. These actions were followed by a number of others, with the Haganah, Irgun Zvai Leumi (IZL), and Stern Gang repeatedly raiding both Rumayma and Lifta. In neighboring Shaykh Badr, the Haganah blew up the house of the mukhtar on 11 January, and two days later launched a second raid in which twenty houses were damaged. Most houses on the eastern periphery of Lifta were also demolished. Morris adds that the purpose of these demolitions was to turn the Palestinian residents out of their homes; to a large extent, this goal was achieved. By 7 February 1948, Jewish Agency chairman (later Israeli prime minister) David Ben-Gurion expressed his satisfaction with the results of the attacks at a meeting of Mapai party leaders: 'From your entry into Jerusalem through Lifta−Romema, through Mahane Yehuda, King George Street and Mea Shearim―there are no strangers [i.e. Arabs]. One hundred percent Jews.'

The settlements of Mey Niftoach and Giv'at Sha'ul were built on village lands and now have become parts of the suburbs of Jerusalem.

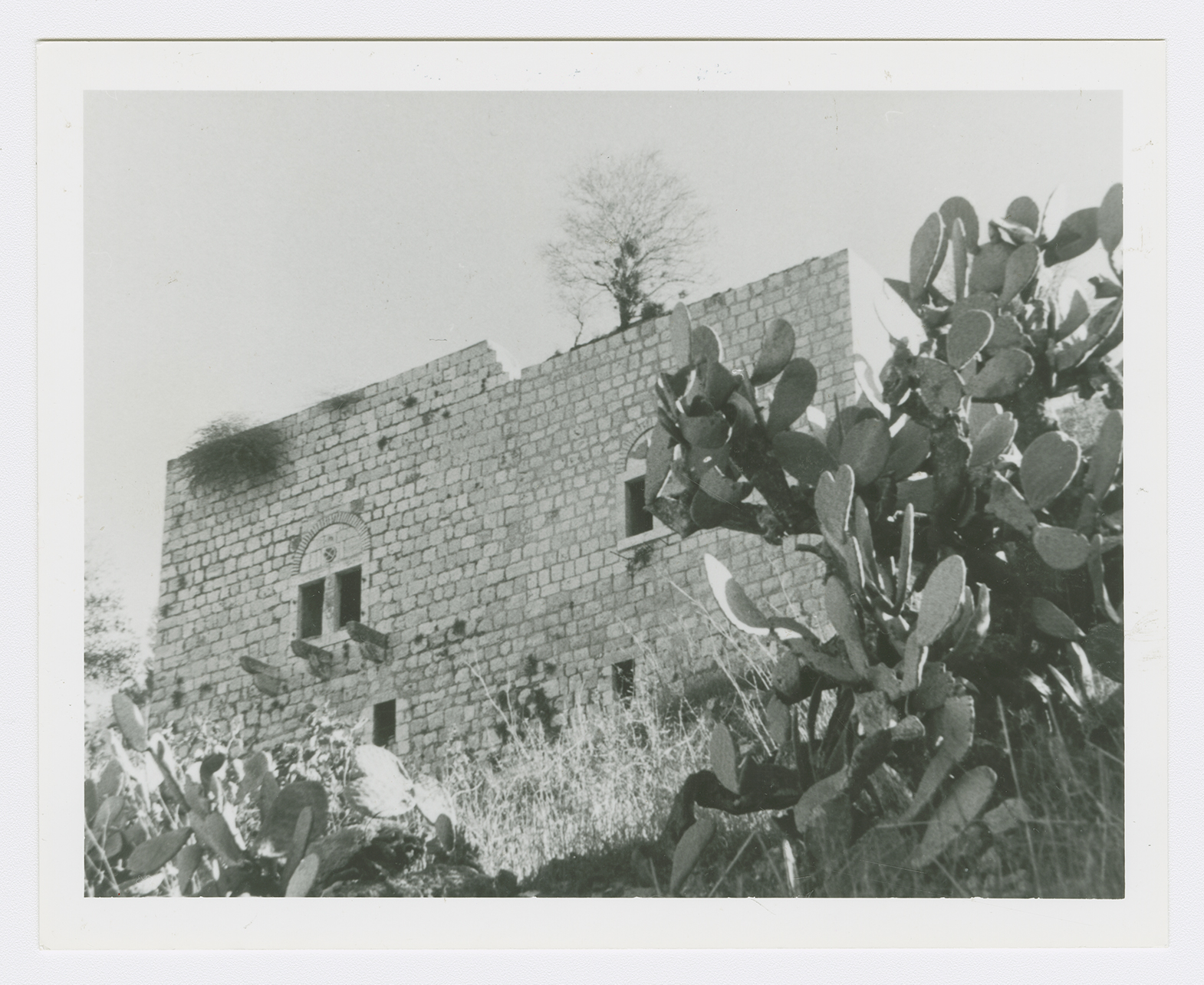

Most of the houses remaining on the site are deserted, although some have been restored for the use of Jewish families. A basin that had been built around the spring in Wadi al-Shami lies in ruins. The mosque and the village club are still visible, north of the spring. Adjacent to the mosque, on the western side, is a cemetery covered with bushes and wild grass. The village orchard of fig and almond trees is located at the bottom of a wadi along a stream flowing from the spring. Jewish families have moved into three of the old village houses. The ruins of other houses are visible in various parts of the site. In 1987, the Israeli Nature Reserves Authority planned to restore the 'long-abandoned village' and to turn it into an open-air natural history and study center that would 'stress the Jewish roots of the site.' This project, with an estimated cost of $10 million, would be financed from donations.

Related Content

Violence

Series of Zionist Attacks on Palestinians in the Wake of the Partition Plan

1947

6 December 1947 - 31 December 1947

The village of Lifta.

Deserted houses in Lifta.

A village house.

Ruins of the village.