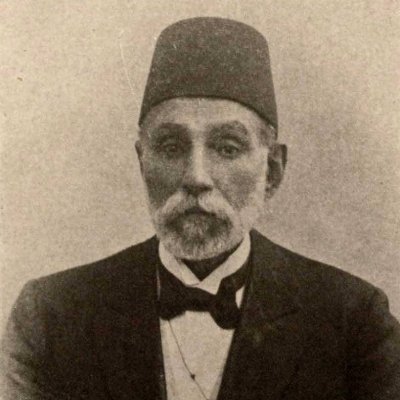

Hafiz al-Sa’id

حافظ السعيد

Hafiz Bek al-Sa’id was born in Gaza City in 1843 to Sheikh Sa’id al-Mustafa. He had two brothers, Mustafa and Asim, and a son, Hilmi.

When Hafiz was born, his father was serving as mutasallim (lieutenant-governor) of the district of Gaza, after having formerly served as mutasallim of the Jaffa district. The origins of Sa’id al-Mustafa’s family can be traced back to a Moroccan family that had settled in Palestine several centuries earlier, and some members held administrative positions in the southern part of Ottoman Palestine since the early nineteenth century.

Hafiz al-Sa’id's father passed away before he reached his first birthday, and he was raised by his elder brother, Mustafa Bek, who followed in their father's footsteps, serving also as the mutasallim of Jaffa and then of Jerusalem in the mid-1830s, during the period of Egyptian rule in Palestine. During his tenure, attempts were made by Jews to purchase land, which prompted Mustafa Bek to obtain a ruling issued by the Jerusalem municipal council affirming that Islamic law did not approve of their purchasing land and that their [economic] rights were restricted to commerce.

In the 1840s, Mustafa Bek was appointed as the officer-in-charge (maʾmur) of the zeptiye (gendarmerie) and the treasury for Jerusalem, Gaza, and Jaffa. Then, during the 1850s, he served multiple terms as the district governor (qa’im maqam) of Gaza. His family eventually settled in Jaffa, where he assumed the position of qai’m maqam in the early 1860s, thus establishing himself as one of the more prominent figures in Ottoman administration and government of the mid-nineteenth century.

Hafiz al-Sa’id received his secular and religious education from the stellar scholars of his time in Jerusalem. He became proficient in both Arabic and Ottoman Turkish and composed beautiful prose and dabbled in poetry.

He began his professional career in the field of public administration; he was appointed as the mudir (local governor) of the Ramla nahiye (village cluster or subdistrict), then as mudir of the Bethlehem nahiye in 1873–1874. He was then promoted to the position of qa’im maqam of the Tulkarm subdistrict, then called Bani Saab. In 1878, Sultan Abdul Hamid bestowed upon him the rank of bala, the highest position in the Ottoman civil service, which entitled him to be addressed with the honorific hadrat sahib al-atufa or “His Grace."

During Sa’id's stint in the Bethlehem subdistrict, a fierce dispute flared in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem between Russian Orthodox monks and Latinate monks over the performing of religious rites and their timings inside the church by adherents of the two denominations. This dispute escalated into an armed clash between the two sides, prompting intervention by Russia on behalf of the Orthodox monks and France in support of the Catholic monks. The Ottoman government entrusted Sa’id with the task of resolving this dispute. He drew up a report specifying the rights of each denomination, which he submitted to the department of religious affairs in the Sublime Porte. The department adopted this report and charged him with implementing his recommendations.

Sa’id later returned to Jaffa, where he was appointed as head of its tribunal of commerce, while also beginning to manage the family’s numerous properties and landholdings. He was then elected twice as a member of the Jaffa administrative council. In 1882, following the revolt by Ahmed Urabi Pasha in Egypt against British-backed Khedive Tawfiq Pasha and foreign intervention to defeat it, and given Jaffa's connection to Egypt by sea, the Ottoman government appointed Sa’id as acting qa’im maqam of Jaffa district on the basis of his competence and decisiveness. He was then appointed mayor of Jaffa city; in this capacity he worked to beautify the city and construct new roads in it. When the German Kaiser Wilhelm II visited the city in late October 1898 as part of his tour of the Ottoman provinces, he conferred upon Sa’id the Order of the Red Eagle, and the Ottoman government also conferred upon him the Order of Distinction-Second Class.

Sa’id was briefly arrested by the Ottoman authorities in 1905 during their crackdown on those involved in the publication of Arab nationalist pamphlets; he was accused of being one of the people disseminating them. After the Committee of Union and Progress Party (CUP) succeeded in taking power and reinstating the constitution of 1876 in July 1908, preparations began in the mutasarrifate (sanjaq, or district) of Jerusalem to elect three representatives to the Ottoman parliament in Istanbul, called the Chamber of Deputies (Majlis al-Mab‘uthan). Hafiz al-Sa’id, Muhammad Ruhi al-Khalidi, and Sa’id al-Husseini were elected to the parliament that convened on 17 December 1908.

In the Chamber of Deputies, Hafiz al-Sa’id demanded that Arabic be adopted by the Ottoman state as an official language. He also raised the issue of Zionist settlement and the sale of land to Jews, and in 1909, he called for the port of Jaffa to be closed to Jewish immigration. It appears that subsequently, he began to frequently absent himself from the sessions of Parliament, preferring to remain in his hometown of Jaffa. In the 2 December 1910 issue of al-Quds newspaper, published in Jerusalem by Jurji Habib Hanania, a letter to the editor from a Jaffa resident was published, criticizing the shortcomings of Hafiz al-Sa’id, the representative of the Jaffa district in the mutasarrifate of Jerusalem “for being negligent in carrying out the duties for which he had been elected, and of spending all his time in his own city." The letter then addressed Sa’id “on behalf of the nation,” urging him to “either return to his office and perform his sacrosanct duty, or to resign and thus spare the nation's treasury the salary he receives from it, for the nation is more deserving of it than he is.” Indeed, the 1908 election for the Chamber of Deputies was the only one in which Sa’id participated; he was not a candidate in the next two elections held in April–May 1912 and in April 1914.

In 1912, Sa’id became a member of the Ottoman Party for Administrative Decentralization, which was founded in Cairo by Arab nationalist emigres from the Levant. The party created a network of “reform committees” in the Arab cities of the Ottoman Empire, especially in Beirut, and Sa’id became the party’s official delegate in Jaffa. The party had the following goals: for Arabic to be made an official language in the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire; for the majority of government jobs in these provinces to be allocated to the local Arab population; for local authorities to be consulted on the appointment of civil servants to these provinces from the central government; for conscripts from these provinces to be able to perform their military service in their local areas during peacetime; and for the powers of the provincial councils to be expanded.

In January 1913, a reform society was created in Beirut, and it held a congress with the participation of eighty-six members nominated from the millet [confessional] councils and religious leaders. The assembly drafted a list of demands under the title “The Reform List for the province of Beirut” that were based on the principle of administrative decentralization. This reformist initiative from Beirut received significant support from some notables in the Jerusalem mutasarrifate, at the forefront of which was Hafiz al-Sa’id, who was by then an active participant in discussions that were taking place around the necessity of reform in that mutasarrifate.

On 19 March 1913, Sa’id sent a cable to the Ottoman Grand Vizier and the Minister of the Interior in Istanbul, requesting that Palestine be included in the policy of administrative decentralization, given its evident importance. The text of his cable included the following paragraph: “We must also come to the realization that after our misfortunes resulting from poor governance and a lack of reform ... Beirut has been forced to request it (reform) and to insist on the expediting of its implementation, and in this way, wrest the homeland from the clutches of foreign ambitions. Since the importance of Palestine is well-known to all, I would consider that any words here to demonstrate this are superfluous. I will suffice with requesting the speedy implementation of these sweeping reforms there, out of the necessity of saving our sacred homeland, which is in the throes of fighting for its life against the disease of maladministration that has become chronic in our realm and is threatening its life. Speedy action is thus a must, and it has become an obligation upon us to aid our realm by carrying out the Beirut Reform List, as it is the only appropriate cure to preserve its life... Therefore, I entreat you to be so kind as to give the order for its speedy implementation.”

Sa’id's cable sparked a widespread controversy in Jaffa. Members of the city’s municipal council, the chamber of commerce, and some spiritual leaders opposed it, denying that he held any authority as a public figure. However, twenty-one of the city’s notables did support what he had written and sent their own cable to the Grand Vizier, in which they stated: "We support the cable of our former deputy, Hafiz Bek al-Sa’id, for the sake of the advancement of our beloved homeland under the aegis of the Ottoman Empire’s banner. We earnestly entreat you to implement the demands of the Beirut Reform List in our district and urge Your Excellency to pay no heed to what certain sycophants, who are desirous for this dire state of affairs to continue, may have propounded to you so as to safeguard their own positions.”

On 27 March 1913, the central government in Istanbul issued a decision to ban the activities of the Beirut Reform Society and for its forum to be shut down. A large-scale campaign was organized in Beirut to protest against this ban, of which Hafiz al-Sa’id was a sympathizer. He expressed his sympathies in an article he penned in al-Quds on 3 May 1913, titled “An Opinion on Reform,” in which he denied the charge of foreign connections leveled at the advocates of reform in Beirut, stressing that reform alone would preserve the Ottoman homeland and safeguard it from the designs of foreign powers. In this article, he states: “It is indeed strange that a certain faction that includes some of our finest writers and senior most government officials, think the worst of the word reform and hear it as an ill omen, believing it to be synonymous with the words ruin and destruction... This faction accuses them [the reformists] of being moved by a foreign hand, even though it is the fear of that hand molesting them that has led them to take recourse in the call for reform... Nay, for it is love of their homeland, the ardent desire to preserve its Ottoman character and safeguard it from foreign designs through implementing reform in it, reform that will uphold and advance the state, that flows in the blood that courses through the bodies of the people of most of the provinces.”

Sa’id was among the Arab nationalists who were arrested in mid-1915 by the so-called “butcher” Ahmad Jamal Pasha, then governor of the province of Syria (bilad al-Sham). They were demanding reform but were accused of collaborating with foreign powers. Sa’id was put on trial in the court of the martial tribunal in Aley in Mount Lebanon. He displayed great boldness during the proceedings of his trial; nevertheless, he was sentenced to death. His sentence was commuted to life imprisonment on account of his old age; however, he died in prison in Damascus Citadel in 1916, and it is believed that he was buried secretly in a location that remains unknown.

Hafiz Bek al-Sa’id was one of the eminent luminaries of the city of Jaffa. He rose to prominence as both an administrator and a litterateur. He sacrificed his life to the struggle for the Arab nationalist demands for reform toward the end of the Ottoman era.

Sources

"أوراق لبنانية". يصدرها يوسف إبراهيم يزبك. الجزء الثاني عشر، كانون الأول/ديسمبر 1955.

حمادة، محمد عمر. "أعلام فلسطين من القرن الأول حتى الخامس عشر هجري، من القرن السابع حتى العشرين ميلادي". المجلد الثاني. دمشق: دار قتيبة، 1988.

الحوت، بيان نويهض. "القيادات والمؤسسات السياسية في فلسطين 1917- 1948". بيروت: مؤسسة الدراسات الفلسطينية، 1981.

الزركلي، خير الدين. "الأعلام: قاموس تراجم لأشهر الرجال والنساء من العرب والمستعربين والمستشرقين". ط 7. بيروت: دار العلم للملايين، 1986.

الشريف، ماهر. "جريدة القدس وبواكير الحداثة في متصرفية أو لواء القدس". بيروت: مؤسسة الدراسات الفلسطينية، 2024.

منّاع، عادل. "أعلام فلسطين في أواخر العهد العثماني 1800 – 1918". بيروت: مؤسسة الدراسات الفلسطينية، 1995.

"الموسوعة الفلسطينية: القسم العام". المجلد الثاني. دمشق: هيئة الموسوعة الفلسطينية، 1984.