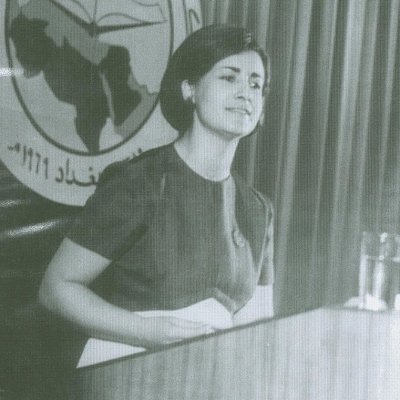

Sulafa Hijjawi

سلافة حجاوي

Sulafa Hijjawi, daughter of Hassan Hijjawi, was born in Nablus. It is said that the poet Ibrahim Tuqan was the one who named her. She married the Iraqi writer and poet Kadhim Jawad, and they had two children: a son, Musʿab and a daughter, Shuʿla.

She studied at al-Aaishiyya School in Nablus up to her third year of secondary school. She had already begun experimenting with writing poetry in her early youth and used to share these poems with the poet Fadwa Tuqan, Ibrahim’s younger sister, who herself had been a pupil of Sulafa’s paternal aunt Fakhriyya.

In 1951, Hijjawi and her family moved to Iraq, where her father worked as a tailor and cloth merchant. She completed her secondary education at al-Rashid School in Baghdad and then enrolled in the Faculty of Arts at Baghdad University. In 1956, she received her bachelor’s degree in English literature with distinction, having obtained the highest grades in the entire faculty. Her name was inscribed on the faculty’s honors board of outstanding students.

In Baghdad, Hijjawi married the Iraqi writer and poet Kadhim Jawad. The poet Badr Shakir al-Sayyab is said to have been one of the witnesses at her wedding ceremony. She became involved in Iraqi cultural life during the 1960s and also began publishing her poems in the Lebanese literary magazine al-Adab.

After the defeat in the June 1967 war, Hijjawi studied political science and worked as a translator and then as a researcher at the Centre of Palestinian Studies affiliated with Baghdad University’s Faculty of Political Science. She was also an editor for the journal published by that center.

While living in Iraq, Hijjawi joined the Fatah movement in 1969. As part of Fatah, she was active in its cultural work and in organizing women, and she established a branch of the General Union of Palestinian Women, which was active among Palestinian refugees living in Iraq.

In April of the same year, Hijjawi attended the ninth Festival of Arabic Poetry that was organized at the conclusion of the seventh conference of the General Union of Arab Writers in Baghdad. The poems she recited there were well-received by the other attendees and were written about in the Arab press covering the festival.

Hijjawi also distinguished herself as a literary translator. The Palestinian novelist and critic Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, who mentored her, acknowledged that she was superior to him in the skill with which she translated major poets, where she maintained a level of precision of expression, imagery, and rhythm in every poem she worked on. Some critics believe that by translating the Palestinian resistance poets into English, she “took the Palestinian battle to the West.”

Hijjawi also took part in the establishment of a union for Palestinian writers and journalists in Iraq, which later became a branch of the General Union of Palestinian Writers and Journalists. In 1983, she was appointed to serve as a delegate for this union to the General Union of Arab Journalists, which in turn appointed her as its delegate to the International Organization of Journalists in Prague.

Hijjawi stopped composing poetry after the October 1973 war; the war greatly disillusioned her. She resumed writing poetry in the second half of the 1980s, after the death of her husband, whom she eulogized with a poem titled “Sufun al-rahil” (Ships of Departure), which became widely renowned.

In 1987, Hijjawi obtained her master’s degree in political science. In 1988, a few months after the First Intifada broke out inside Palestine, she decided to resign from her position at the Faculty of Political Science at Baghdad University and move to Tunisia, where the PLO was now based. There, she worked as Director of Political Affairs in the office of the chairman of the Executive Committee of the PLO, Yasir Arafat. She was one of Arafat’s four advisors; after that, she took over the management of the Palestinian Planning Center in Tunis.

In 1994, after the signing of the “Gaza-Jericho I” agreement [as part of the Oslo Accords], Hijjawi returned to Palestine and lived in the Gaza Strip. She moved the Planning Center along with her, supervising its re-establishment in Gaza, and continued to manage it until her retirement in late 2005, when she moved to Ramallah.

After her retirement, Palestinian journalist Mohammed Kreizem conducted a lengthy interview with her at her home in Ramallah about her career as a poet and the issues around Arabic poetry, during which she observed:

The 1950s saw the beginning of my early experiments in writing poetry, which at the time were short pieces. It was only from the late 1960s that I launched myself as a poet. My orientation was toward my national cause. Therefore, all my poems, that came to be known throughout the Arab world, were characterized as being nationalist poems of a special color and flavor, with a great deal of subjectivity. I was greatly influenced by my love of photographs and drawings, so my poems took on more of the form of paintings than the narrative style adopted by many other poets. I published my first collection of poetry in 1975 during the Congress of Arab Writers. At the time, the newspapers from every corner of the Arab world “from the Gulf to the Atlantic” as the saying goes, wrote about me as heralding the birth of the greatest woman Arab poet. However, I let them down because I became preoccupied with political issues and turned to academic scholarship for certain reasons. I returned to poetry starting in the mid-1980s and since then have written poetry in a new style.

When asked about her stance on revolutionary poetry that is meant to rouse the masses to action, she commented: “There is no doubt that poetry comes out of feeling, especially in Arabic where the two concepts (shiʿr and shuʿur) are etymologically linked. Therefore, poetry cannot be limited to its capacity of mobilizing people to action. Revolutionary poetry does have a specific role to play, but it is a limited one, and good poetry is that which is contemplative, poetry that reflects ideas from reality that express humanist values. Revolutionary poetry will always be limited to a specific time period unless it considers more profound human sentiment.”

When asked about why the genre of shiʿr al-muqawama, or resistance poetry, arose inside Palestine and not outside of it, she replied: “The challenges were different; inside the homeland there was the occupation and we were there, standing up directly to the occupier as Palestinians firmly rooted in our land. Outside Palestine, however, the situation was catastrophic—we were a dispersed people; each and every one wanted to prove his sense of self, as if to say: ‘I exist.’ This was the initial stage of diaspora, which later evolved into resistance. There is a difference, therefore, in the types of challenges that were confronting people inside Palestine and those outside of it.”

Regarding what sets apart that which is particularly Palestinian or Arab in poetry from that which is universal in poetry, she said:

Poetry is either universal, or it isn’t—that’s my opinion. By that, I mean that the poetry you write embodies your particular sense of self, whether you’re a Palestinian or a citizen of any other country, yet simultaneously it expresses concepts that people all over the world can comprehend and grasp. This is poetry that is universal. The universality of poetry does not mean writing about things far removed from your lived reality, not at all! Look at the great poet [Federico Garcia] Lorca and the tiny, minute details from the life of the Gypsies that he writes into his poems. Yet Lorca fully deserves to be considered “universal,” because any reader of poetry anywhere in the world will comprehend him and his poetry will resonate with them. This is because through this particularity in his poems, Lorca expresses universal sentiments, pain and dreams that are comprehensible to any human being in any corner of the world. Universality does not clash with particularity, provided it is clothed in creativity.

When asked if women’s issues occupied a space in her poetry, she replied, “No, I have never written poetry in that way. I don't believe in demanding rights for women, but rather in seizing them. Women should engage in struggle, not just make demands. That is why I never wrote anything in which I demanded rights for women. I’ve always taken my rights; I’ve seized them with my ability, proficiency and skills. A woman who doesn't fight for her rights will lose those rights. Yes, women have been denied their rights, and I believe that Palestinian women haven’t gotten what is rightfully theirs, but Palestinian women shouldn’t withdraw or retreat into themselves.” Regarding the contribution of women in Palestinian poetry, she remarked: “The overall number of women poets in the Palestinian arena is small; this is a reflection of reality, because writing poetry requires psychological freedom, and women in our society, generally speaking, don’t enjoy this freedom. In addition, poetry requires having cultural awareness. While Palestinian women may (broadly speaking) have emotions coursing through them that they wish to express, they are unable to express them in the required manner, for the opportunity afforded in our society to women to do that is still very minute.”

Jamal al-Baba, one of Hijjawi’s early colleagues in the Gaza Strip when she reopened the main office of the Planning Center, said of her:

She was deeply interested in translation and also paid marked attention to local politics in all aspects. Through the center’s various departments, she also was attentive to issues concerning negotiations, as well as Israeli, American and regional affairs. . . . Hijjawi was in constant communication with the Palestinian leadership, providing them with her assessments of the current state of affairs. She also started the Planning Center’s journal, which became one of the most important scholarly journals in the field of politics, and remained its editor-in-chief until her retirement. In addition to all she did, she also possessed strong leadership and administrative skills.

Hijjawi passed away on 14 September 2021 in Ramallah after a long illness. Both Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas and Minister of Culture Atef Abu Saif mourned her passing. Abu Saif said: “The militant and lady of letters Sulafa Hijjawi played a pioneering role in the Palestinian struggle for national liberation, whether through her political role within the PLO, her role as an educator through her long work in the field of teaching and higher education, or her creative role through her career as a poet, literary writer and translator. Through all these different roles she played, she contributed to consolidating the presence of the Palestinian cause for us, making its presence a reality in various forums.” The General Union of Palestinian Writers also mourned her passing in a statement released by its general secretariat: “How painful a blow the departure of the militant poet and translator Sulafa Hajawi to the immortal hereafter is, can be gauged with how much she gave to her stolen homeland, and whose cause she lived for as a long-standing freedom fighter and artistic creator, devoting her entire life to a higher purpose, that of her nation. For the entire duration of her life, she was at one with her people, living through their sorrows with them.” The secretariat added in its statement that the deceased “was one of the batch of front-runners who founded the General Union of Palestinian Writers and Journalists, and that she carried out her tasks with complete dedication and capability.”

Sulafa Hijjawi was a poet, scholar, and militant activist. Her death in 2021 brought to an end a long career as both artist and activist, one that encompassed poetry, translation, and political activity and contributed to consolidating the presence of the Palestinian cause on both the Arab and international levels.

On 27 October 2021, a memorial service was conducted at the Yasir Arafat Museum in Ramallah to mark the fortieth day since her passing. The ceremony was organized by the PLO’s Planning Commission, the Ministry of Culture, Ministry of Information, Palestine TV, and the General Union of Palestinian Writers. A short film about Hijjawi’s life was screened, in which her poems, writings, and translations were featured. Friends, colleagues, and relatives spoke about her life, reminiscing about her and praising her personal qualities, her vision, goals and ideas, and her role in the Palestinian struggle.

Selected Works

Poetry Collections

"أغنيات فلسطينية". بغداد: وزارة الثقافة العراقية، 1977.

[Palestinian Lyrics]

"سفن الرحيل". رام الله: وزارة الثقافة الفلسطينية، 1998.

[Ships of Departure]

"حلم، شعر للأطفال": رام الله، مؤسسة تامر للتعليم المجتمعي، 2008.

[Dream (poems for children]

Studies

"اليهود السوفييت – دراسة في الواقع الاجتماعي". بغداد: جامعة بغداد، 1980.

[Soviet Jews - A Study of their Social Reality]

"النفط والجيوستراتيجيا المعاصرة". غزة: مركز التخطيط الفلسطيني، 1998.

[Oil and Contemporary Geo-strategy]

"تجربة جنوب أفريقيا". غزة: مركز التخطيط الفلسطيني، 1999.

[The South African Experience]

"في التاريخ السياسي لفلسطين". غزة، [المؤلف]، 2000.

[On the Political History of Palestine]

Translations into Arabic

Lorca, Grenada’s Lyre (co-translated with Kadhim Jawad). Baghdad Printing, Publishing and Distribution, 1957.

David Sinclair, Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Work. Baghdad, 1982.

C.M. Bowra, The Creative Experiment (2nd ed.). Baghdad: Dar al-Shuʾun al-Thaqafiyya, 1986.

Paul Hernadi, What Is Criticism? Baghdad: Ministry of Culture and Information, 1998.

Gabriel Piterberg, The Returns of Zionism: Myths, Politics and Scholarship in Israel. Ramallah: Madar Palestinian Center for Israel Studies, 2009.

Translation into English

Poetry of Resistance in Occupied Palestine. Baghdad: Ministry of Culture, 1968.

Sources

Descamps-Wassif, Sara. Dictionnaire des écrivains palestiniens. Paris: Institut du monde arabe, 1999.

دياب، امتياز، "هل تعرفون سلافة الحجاوي؟"، "السفير العربي"، 25 كانون الثاني/ يناير 2018.

https://assafirarabi.com/ar/19003/2018/01/25/هل-تعرفون-سلافة-الحجاوي؟

حافظ، عزام، "سلافة حجاوي...تحدثت بصوت الوطن ورحلت بصمت"، "فلسطين أونلاين"

https://felesteen.news/post/94467/سلافة-الحجاوي-تحدثت-بصوت-الوطن-ورحلت-بصمت

شبكة نوى، "وفاة الشاعرة سلافة حجاوي: حكاية قلم عاش ’صاخباً’ ورحل ’بصمت’، 14 أيلول/ سبتمبر 2021.

https://www.nawa.ps/ar/post/46921

علي، ياسر، "سلافة حجاوي...حملت اسم فلسطين في كل منافيها". "عربي 21"، 22 كانون الأول/ ديسمبر 2022.

https://arabi21.com/story/1480138/الشاعرة-سلافة-حجاوي-حملت-اسم-فلسطين-في-كل-منافيها.

كريزم، محمد، "الأديبة الشاعرة الفلسطينية سلافة حجاوي: زمن أمراء الشعر إنتهى ... الشعر المسرحي ضعيف لغياب المسرح نفسه". "الحوار المتمدن"، 10 أيار/ مايو 2007.

https://www.ahewar.org/debat/show.art.asp?aid=96261

الميادين نت، "رحيل الشاعرة والمترجمة الفلسطينية سلافة حجاوي".

https://www.almayadeen.net/culture/رحيل-الشاعرة-والمترجمة-الفلسطينية-سلافة-حجاوي

Related Content

Institutional Policy-Program

Palestine Liberation Organization (I)

The Reemergence of the Palestinian National Movement